Translated by: Nooshin Karimi

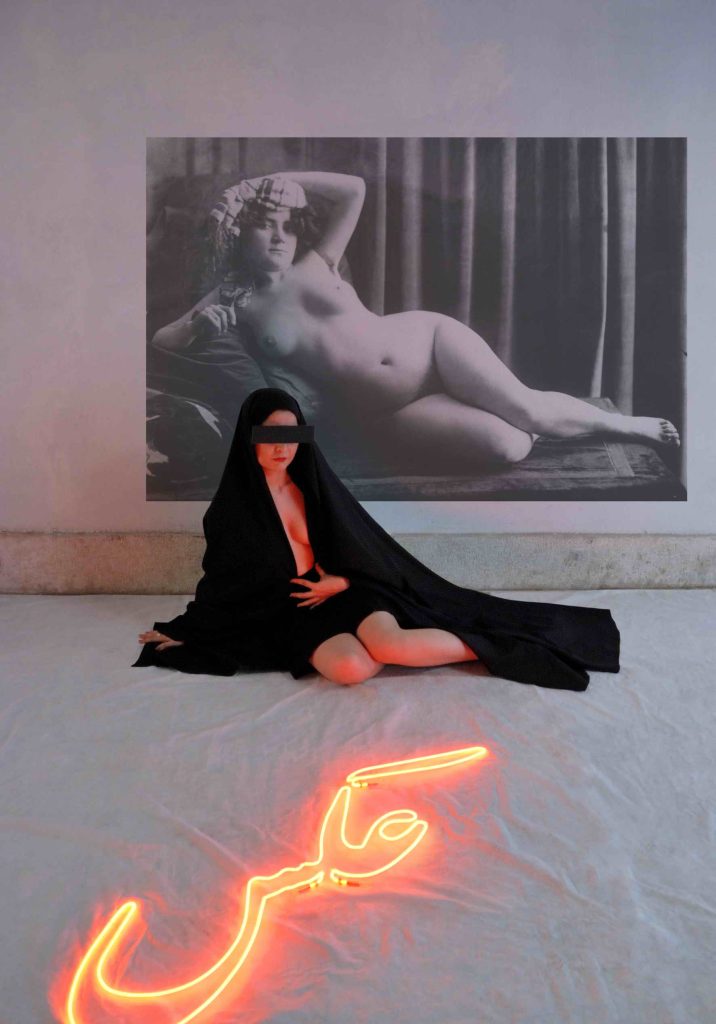

“The truth need not to be defined. It flows in world’s length and width and since light is such explicit verity, the rest of the words are explained by it.” In some of the late works of Arman Stepanian this poetic saying of the martyr sheikh, Shahāb ad-Dīn” Yahya Suhrawardī, is vividly present. A trace of light on the blasé world; despite a faint fleeting hope for the subjects to perpetuate to live within the frames, the photographer would viciously throw the truth in its face. Here is no place to faithfully record the world’s reality but somewhere to express what is true over any question. The dominant elements in frames include the confrontation of time with the human desire for immortality and light which could not even save the martyr sheikh. The photographer is neither looking for his lost self nor is after a position among the world’s significance. He keeps observing. He is watching the melancholic fast pace of time and this insane human tendency towards death accompanying him ever since his birth. However, when the photographer rubs the truth in the viewer’s face, he becomes less of an observer and an objective for some seconds. In one of the pictures, there is a woman half naked in oriental clothes, sitting on the ground looking not exposed nor wrapped! This level of similitude of a woman being both covered and undressed is a pure Eastern characteristic rooted in the disastrous history of a creature whose body is more of a weak point for an offender than a device working for her mind. In other words, her history is not written by herself but by the male. In the photographer’s most revealing arrangement, the woman is neither naked nor in hijab! This is still not the whole truth he is trying to observe. Despite being disclosed, there are no signs of change in his motifs. Behind the ethereal woman’s head, whose eyes do not even get the chance to flirt, there is another woman sprawling on a cushion gazing ahead in a black and white photo. A woman from the timeless past. Both are posing alike, staring ahead, one exposed and the other wrapped in an emblematic dress. The woman from the past is an obvious sexual object left against the frame and the second, Setepanian’s creation is holding some type of opacity that cannot be comprehensively defined despite all said. However, what difference does it make when death, the inevitable destiny of the woman in the frame, is in the hands of the woman made by the photographer?! Rather than reminding us of constancy, they both provoke bitter human interactions. Perhaps, a century from now someone will add a third woman to the frame and complete the melancholic chant of these women. It seems cruel of the photographer to lay the observer open to time in this series.

info@armanstepanian.com

+989362835579

©Artizen Web All Rights Reserved.